Mechanical Back Pain

Mechanical back pain is a general term describing pain caused by the day to day stress and strain on the structures of the spine that can not be accommodated by your body, rather than being caused by a structural abnormality.

It accounts for approximately 95% of all back pain and includes pain produced by the joints, ligaments, discs, muscles and the relationship between all these structures that make up the spine.

Causes

The specific cause and/or source of the pain usually cannot always be identified and often has multiple contributory factors. This may include:

- Poor muscle control or muscle imbalance around the spine

- General lack of physical fitness so that your body is unable to distribute normal stress and strain forces

- Poor posture

- Poor seating or a sedentary lifestyle

- Incorrect bending and lifting actions.

Symptoms

- Pain in lower back

- Pain radiating down into the buttock and/or leg

- Muscle spasm

Diagnosis

This is established by your history, pain behaviour, and physical examination. If there are no signs of nerve pinching or irritation eg weakness, tingling or numbness, it is most likely your pain is “mechanical back pain”.

Mechanical back pain is often diagnosed instead of spondylosis or degenerative discs, as these conditions commonly occur together. However, the treatment remains the same for these conditions.

No further testing or investigations are necessary unless the doctor suspects a cause other than “mechanical pain”

Treatment

Mechanical back pain responds best to conservative management which is very effective is resolving symptoms.

- Heat/ice (can alternate both 20 min 2-3 x/day)

- NSAIDs (Advil/Ibuprofen) or over the counter pain relief (Tylenol/Acetaminophen) medication

- Muscle relaxants may be indicated for some

- Positive attitude (mindfulness/meditation)

- Massage therapy

- Physiotherapy

- Spinal mobilisation/manipulation

- Maintain physical activity – e.g. walking, swimming. Whatever activity is chosen it should be performed with “pacing” eg start slowly (baseline) for a short time that you can do on a good or bad day. Increase gradually over time, in line with what you can manage without aggravating your pain

- Maintain regular activities where possible and/or return to normal activities promptly

A physiotherapist, evidence-based chiropractor or other therapy professional can help inform you on the possible causes and educate you about beneficial postural changes, strengthening and stretching exercises for your back and core muscles. Evidence exists showing that activity over rest or passive treatments is the best course of action, and an individualised plan for returning to your activities of daily living and work as required can be helpful. A home program encouraging regular long term active exercise has been shown to be the most effective treatment approach.

Spinal surgery is not indicated for mechanical low back pain.

Spondylosis/Degenerative Discs

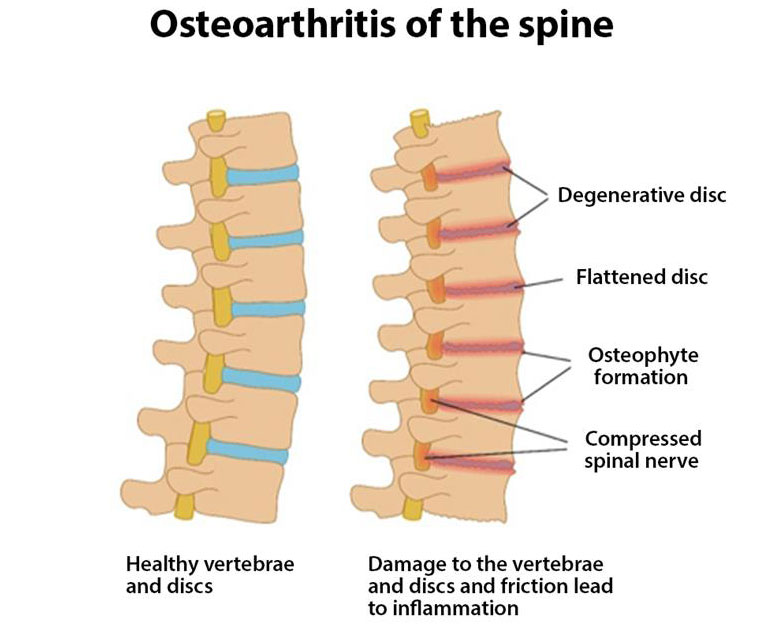

Spondylosis is caused by normal age-related changes of the vertebrae and discs of the spine. It may also be called degenerative disc (disease), osteoarthritis, or wear and tear. It can be present anywhere in the spine as a result of natural aging processes, but it most often occurs in the cervical (neck) and lumbar (low back) spine because these areas carry most of the work asked of the spine.

Spondylosis is caused by normal age-related changes of the vertebrae and discs of the spine. It may also be called degenerative disc (disease), osteoarthritis, or wear and tear. It can be present anywhere in the spine as a result of natural aging processes, but it most often occurs in the cervical (neck) and lumbar (low back) spine because these areas carry most of the work asked of the spine.

Cause

Degeneration occurs in all our bones and joints over time. It is an inevitable part of aging. The degenerative process starts in people in their 20s, and 80% of women and 95% of men over 65 years have evidence of such changes on imaging.

It may mean the roughening of joint surfaces, the weakening and thickening of ligaments attaching onto the spine, or the development of spurs on the margins of the bones which can protrude into joint spaces. The discs may also dehydrate, making them thinner and less flexible and hence less able to shock absorb, which can then increase the loading on other structures e.g. the joints.

Symptoms

Spondylosis often has no symptoms, although localised discomfort can sometime be felt that is usually worse after periods of inactivity e.g. in the morning or after prolonged sitting, and better after movement or as the day goes on. Degenerative changes may contribute to other conditions that may cause pain e.g. Spinal Stenosis.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually established based on your history, symptoms and a physical examination. In most cases, conservative management is the best course of treatment, and imaging is rarely required unless it will direct a change to your plan of care.

Treatment

Conservative treatment is usually all that is necessary to treat spondylosis/degenerative change.

- Heat/cold application

- NSAIDs (Advil/Ibuprofen) and/or pain relief (Tylenol/Acetaminophen) medications

- Muscle relaxants (although there is limited evidence to support their use, they can be useful on a case by case basis)

- Physiotherapy or evidence based chiropractic, to provide postural and lifestyle education and appropriate stretching and strengthening exercise which will improve your general fitness, build strength, endurance and general flexibility for your spine and core. A home program will be provided to help you self-manage your symptoms.

- Cardiovascular exercise (walking, cycling, swimming)

- A positive mindset (e.g. meditation/mindfulness)

- Daily exercise to stretch and warm up to activity for the day

- Weight loss

Spinal surgery is not indicated for spondylosis/degenerative changes

You can try the following basic exercises for this condition. If they aggravate your symptoms, please discontinue and seek advice from a health professional.

Spinal Stenosis

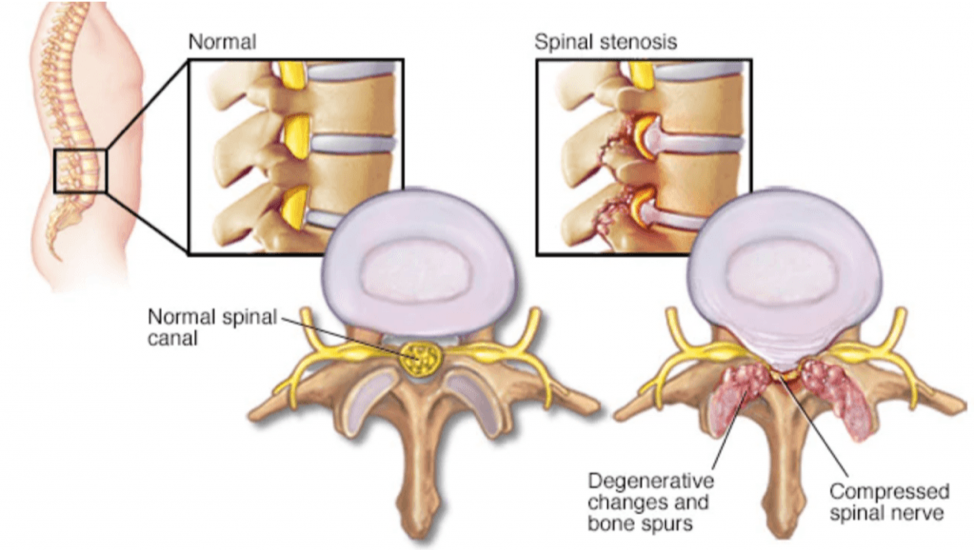

Spinal stenosis is a narrowing of the spinal canal, usually caused by degenerative changes E.g. arthritic changes including the development of bone (spurs), disc herniation as the discs age and dehydrate, and tissue thickening (ligaments) which take up more space within the spinal canal, leaving less available for the nerves. Alternatively, stenosis can occur at the neural foramina (tunnels that the nerves exit through near the facet joints), reducing the space available for the spinal cord and /or the spinal nerves as they branch out and exit from the spinal cord. The nerve structures become irritated or physically pinched. As these nerves supply the extremities and not the back/neck, the condition does not usually cause neck/back pain. It usually causes radiating arm/leg pain, weakness, and/or tingling or numbness that radiate down one or both arms/legs. This is known as neurogenic claudication.

If stenosis occurs in the neck it can cause compression of the spinal cord which is known as myelopathy. In addition to the pain detailed above, there may be unsteadiness when walking, poor coordination, dexterity and balance. Myelopathy may require urgent specialist intervention and possibly spine surgery.

Causes

- Age-related degenerative changes in spine

- Previous spine surgery or injury

- Thickened ligaments

- Spurs that form and or joint swelling from osteoarthritis

- Heredity/Genetics

- Disc herniation

- Severe Scoliosis

Symptoms

- Pain radiating down the entire leg (or both legs) (This could also occur in the neck with pain radiating into the shoulder, arm and the hand)

- Intermittent cramping, weakness, tingling, and/or numbness in leg(s) (arms)

- Worse with standing and walking, and activities including leaning backwards

- Difficulty walking due to difficulty feeling or coordinating legs, or weakness

- Stooped posture, as feels more comfortable

- Better with rest, sitting or leaning forwards

- Poor balance

Neurogenic claudication is the most common symptom of spinal stenosis. It is usually relieved by forward bending in sitting or standing, squatting or lying down, because it “opens” the canal space and gives the nerves extra room (thereby reducing the pinching or irritation).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made based on your history, symptoms, pain behaviour with activity, and physical examination. Imaging such as X-ray or MRI may be required, but usually this is only in patients with leg dominant (leg>back pain) symptoms to confirm diagnosis when it is believed treatment beyond conservative management is required.

Treatment

Symptoms are best managed with conservative treatment such as physiotherapy. Evidence exists showing that a rehabilitation treatment course focusing on exercises encouraging forward bending, core strengthening and pacing of general activity, is just as effective as surgery for spinal stenosis with far less adverse side effects.

Conservative treatment- Activity modification e.g. pace yourself and separate activity into shorter periods, with time to sit or do bending exercises in between bouts of activity.

- NSAIDS (Advil/Ibuprofen) and/or pain relief (Tylenol/Acetaminophen) medication

- Medications that specifically help decrease nerve pain can be helpful (e.g. Lyrica, Gabapentin). These need to be taken regularly as prescribed, not just when you feel bad. Titration (gradual increase in dosage) is also usually required.

- Exercise and stretching

- movements that encourage forward bending (flexion)

- avoid back bending (extension)

- Physiotherapy / Evidence based chiropractic

- Daily graded exercise to improve physical condition/fitness

- walking with a gait aid or Nordic poles

- bicycling

- aquafit

- Massage

- Acupuncture may be beneficial

- Heat

- Weight loss

- Good posture

Rehabilitation should focus on active exercises that encourage forward bending, maintenance/improvement of the flexibility and stability of your spine to help take pressure off the nerve roots and help decrease pain. You are also encouraged to do exercises that will build up your strength, endurance and balance (e.g.: stationary bicycle, swimming/aqua-fit, Tai Chi are the best recommendations for this condition). You will also likely discuss your postural habits and look at how you stand, walk and sit. A personalized home exercise program will help you self-manage your symptoms.

You can try the following basic exercises for this condition. If they aggravate your symptoms, please discontinue and seek advice from a health professional.

Surgical treatmentSpine surgery may be required if there is significant pinching of the nerves (causing leg dominant pain) that is limiting your ability to function and quality of life significantly (unable to walk even short distances) e.g.

- The muscles around your pelvis and upper legs become weak

- It becomes difficult to control your bowel or bladder

- pain can’t be controlled by medicine and exercise

Usually patients need to have trialled a good quality conservative management plan including all the recommendations above for at least 3 months before spine surgery is considered, and the primary indication is the neurogenic claudication (leg pain) vs back pain.

The best candidates for successful spine surgery are those whose pain eases with forward flexion, with less widespread areas of stenosis, and who are medically well.

A decompression or in some cases a laminectomy is performed. This involves the removal of a small amount of the bone and tissue that is compressing the nerves to maximise the available space inside the spinal canal or neural foramen. It is often done as a day surgery and you can return to normal daily activities within 2-6 weeks.

Spinal fusion may be performed if there needs to be more extensive tissue removal that may compromise the stability of the spine. This involves the insertion of screws, a small cage, or other metalwork that supports the spine. You will be in hospital for a couple of days following this procedure and recovery to normal activities will take approximately 12 weeks.

Rehabilitation after spine surgery will be dictated by your surgeon. Usually it is advocated to do physiotherapy or other therapies that focus on progressive back and core strengthening exercises and graded return to functional stresses.

Discogenic low back pain: without Sciatica

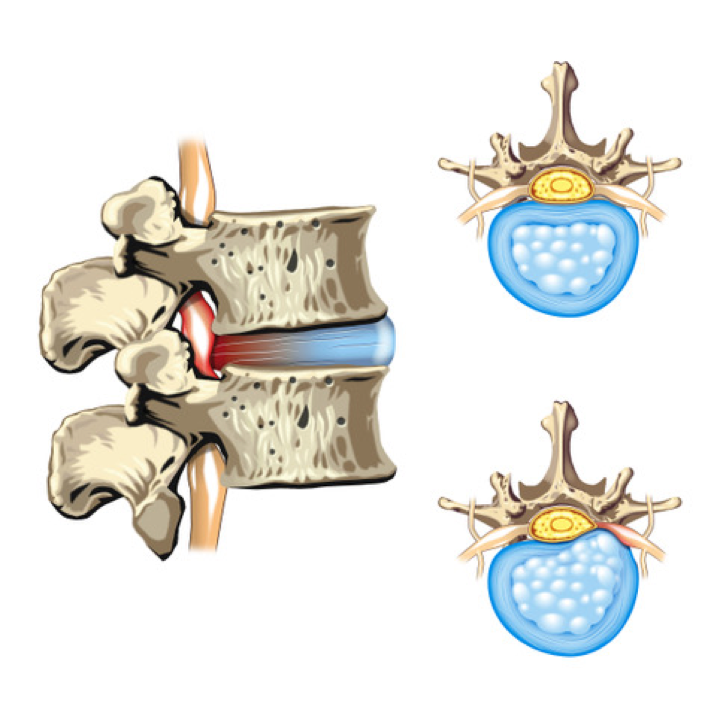

The disc sits between the vertebrae, acting as a shock absorber. It also distributes stress evenly to resist stress and strain. It consists of two parts: an inner distortable semi-fluid gel centre (nucleus pulposus) and the strong, ligamentous ring (annulus fibrosus) that surrounds it. There is no blood flow to the disc which limits its ability to heal when injured.

The disc sits between the vertebrae, acting as a shock absorber. It also distributes stress evenly to resist stress and strain. It consists of two parts: an inner distortable semi-fluid gel centre (nucleus pulposus) and the strong, ligamentous ring (annulus fibrosus) that surrounds it. There is no blood flow to the disc which limits its ability to heal when injured.

Discs can become injured through continuous or repeated stresses in one area, causing some of the inner gel to herniate or bulge against, or through the annular wall, causing the disc material to protrude beyond the margins of the bones. This is commonly called a “slipped disc”, disc bulge or disc protrusion/herniation. The outer wall of the annulus contains many nerve fibers that may be affected by an injury and cause pain. Due to the position of the disc close to the nerve roots exiting the spine (which then supply your arms or legs) it is possible the disc injury may “pinch” the closest nerve root. Alternatively, the disc injury may create inflammation which can “chemically” irritate the nerve rather than physically compress it. Either of these processes may disrupt the normal messaging of the nerve eg change your sensation, reflexes and strength or create radiating pain along the rout of the nerve. This is called radiculopathy (eg sciatica) and is discussed in the next section.

Disc bulges are normal and at least 25% of the population has them without any associated symptoms. However, those who do experience discogenic back pain are commonly aged 30-60 years old.

Approximately 80-90% of patients with an acute episode of discogenic back pain will recover with conservative management over time (approximately 12 weeks).

Cause

- Repetitive or prolonged bent over, or bend and twist activities

- Poor posture

- Injury or trauma

- Smoking - research shows an increased incidence in smokers

- Poor core muscle control around the spine

- Sedentary lifestyle: prolonged sitting, reclined or slouch sitting

- Obesity

Symptoms

- Decreased movement in your back due to pain, often into bent positions

- Low back pain with or without pain referred down the leg can be felt anywhere from the buttock to the foot (Less commonly this condition may also affect the neck and arm)

- Abnormal sensation eg pins and needles or numbness in the leg

- Pain quality is burning or cramping

- Weakness in leg or foot

- Worse with sneezing or coughing, sitting or bending

- Worse in the morning

Diagnosis

Your history, pain behavior and physical testing are the biggest indicators of potential disc related pain. There is usually no need for an X-Ray unless your back pain is due to a fall, accident or other trauma.

An MRI is unnecessary unless your pain is leg dominant eg the leg pain is worse than the back pain. Also if it has been present for more than 3 months, is unchanged by good quality conservative treatment, you have associated sensory change, weakness or reflex changes, and there is a need to evaluate if spine surgery or other interventions are required.

Treatment

Conservative- Activity modification including:

- Avoid bed rest

- Avoid prolonged sitting

- Stay active – go for several short walks during the day or do other exercise as able

- Maximize good posture: Choose straight backed/firm chairs and use a small pillow, rolled up towel or lumbar roll in the small of your back to maintain the natural arch of the low back.

- Education on condition and appropriate treatment (as stated here)

- Positions of relief – when in pain use any posture or position you find lessens pain for short periods e.g. laying flat on your stomach.

- Apply cold or alternating hot/cold (15-20 minutes, every 2 hours)

- NSAIDS (Advil/Ibuprofen) and/or pain relief (Tylenol/Acetaminophen) medication

- Physiotherapy

- Strength and stabilizing exercises

- Extension exercises (bending backwards) are often most effective

- McKenzie method: a therapist led system of assessing patients and then prescribing specific and appropriate exercises based on your symptoms. This method has been shown to produce better results than non-specific generic therapy and exercises.

- Acupuncture

- Spinal mobilization in some patients

- Ergonomic workplace assessment

- Exercise and paced general physical activity (walking, swimming)

It is important to remain as active as possible by taking frequent short walks, doing your rehabilitation exercises, swimming or other activity that is comfortable to undertake. Pacing activities is important: find a comfortable baseline you can do regardless of whether it is a good or bad day, and over time slowly build up. Movement will decrease pain and stiffness and help you feel better more quickly. Together with lifestyle changes in the short term, this is the most effective method of managing acute pain.

Medication may also be required if you have nerve related pain, as this will target the “cause” of the problem and allow you to recover more quickly.

Hurt does not equal harm. It is possible that some activities can still be done with some pain without them causing damage or injury eg you may have pain from stiffness due to inactivity that will ease as you become more active. This includes a return to work if you have been off, although you may benefit from guidance with this from a rehabilitation therapist eg physiotherapist.

You can try the following basic exercises for this condition. If they aggravate your symptoms, please discontinue and seek advice from a health professional.

Surgical treatment

Spine surgery is not indicated for discogenic back pain without sciatica.

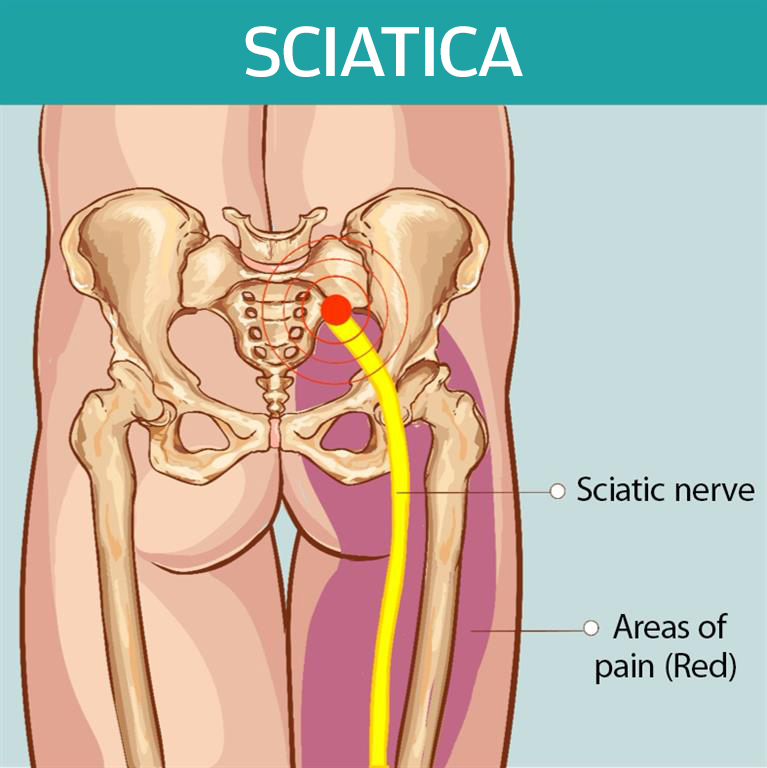

Sciatica/Radiculopathy

Sciatica is an umbrella term to describe a group of symptoms and not a specific condition. It refers to pain that radiates from your back down the leg due to irritation of the nerve roots that branch off your spinal cord and run down your legs. Typically, the pain will radiate down one side only. It can be mild to severe.

There are multiple causes of sciatica including:

- A disc bulge or herniation

- Spinal stenosis

- Spondylolisthesis

- Piriformis syndrome

- The sciatic nerve can become irritated as it runs through or under the piriformis muscle in the buttock, which reproduces pain that feels like sciatica. The piriformis muscle is a small triangular muscle that is located deep in the buttock. It can become tight and irritate/compress the sciatic nerve that runs nearby causing pain/numbness/tingling in the buttock and leg as far as the foot.

- Tumor

- Infection

- Disease -such as Diabetes

Symptoms

- Pain located on one side from low back to your buttock, thigh and calf

- Leg pain can be mild to excruciating and constant or intermittent

- Can feel like an electric shock, cramping or burning

- Worse with coughing or sneezing

Treatment

Sciatica pain will often subside and go away over time with no more than conservative treatments (minimum 12 weeks).

Sciatica pain will often subside and go away over time with no more than conservative treatments (minimum 12 weeks).

- Activity modification

- Education

- Heat/ice (20 min 2-3 X/day – you may alternate)

- Oral (Advil/Ibuprofen) or topical (Voltaren emulgel) NSAIDs and/or pain relief (Tylenol/Acetaminophen) medication

- Muscle relaxants may be of benefit

- If leg dominant symptoms are present specific medications (neuroleptics) to limit nerve pain (e.g. Pregabalin/Lyrica, Gabapentin) can be beneficial. These need to be taken regularly as prescribed, not only when you feel bad. Titration (gradual increase in dosage) is also usually required.

- Exercise (walking, swimming) within comfortable limits, progressing as able

- Physiotherapy or evidence based chiropractic

- Spinal mobilisation

- Acupuncture

- Massage therapy

- Ergonomic workplace assessment

You can try the following basic exercises for this condition. If they aggravate your symptoms, please discontinue and seek advice from a health professional.

Surgical treatment

Spine surgery for sciatica due to lumbar disc herniation is performed only if you have leg dominant pain (more leg > back) because of a pinched nerve. The aim is to “un-pinch” the pinched nerve by removing the disc material that is causing irritation and/or compression. This is called a discectomy.

This is usually done as a day case surgery and involves a small incision normally approximately 1-1.5 inches in length. Occasionally this may be combined with a decompression procedure, where a small amount of bone in the area of the disc herniation is also removed to reduce the likelihood of future recurrence.

Normally recovery takes a couple of weeks, with return to work in 2-4 weeks if you have an office job and 4-8 weeks if your work involves physical labour. There is a good success rate for significant reduction of leg pain or other symptoms, although it has also been shown that at 2 years and 5 years after onset of disc related pain, those who have spine surgery and those who don’t generally report the same functional ability level and pain.

Spondylolysis / Spondylolisthesis

Spondylolysis is a naturally occurring defect, crack or stress fracture that develops in the pars intercularis, a thin bony bridge on the back of the vertebra where the facet joins to the body of the vertebra.

It can occur in people of all ages however; children and adolescents are more vulnerable because they are still growing, and their spine is not finished developing. It is more common in young athletes who practice sports that put repeated stress on the lower back, such as gymnastics, weight lifting, wrestling and football. It most commonly affects the vertebral levels in the low back. (L4/5 and L5/S1).

Spondylolisthesis occurs when one vertebra slips out of position in relation to the one above or below. Usually this slip occurs in a forward direction. It occurs most commonly in the lumbar spine at the L5-S1 level but can also occur in the cervical spine.

Depending on the amount of movement, it can be categorized as a low or high grade spondylolisthesis. High grade slip occurs when more than 50% of the vertebrae has moved out of alignment.

The presence of spondylolisthesis does not necessarily mean it is problematic. Most are asymptomatic and usually low-grade and stable with no treatment required.

Causes

There are several different causes:

Congenital spondylolisthesis is an uncommon condition and present at birth as an anomaly. This is more common in females. The spine usually adjusts and adapts to the deformity.

Isthmic spondylolisthesis is caused by a defect, crack or fracture in the pars interarticularis; a thin bony bridge which exists between the facet joints and the body of the vertebral bone. This usually developed during adolescence. The stability of the bone may be affected leading to the positional change. This most often occurs in highly active adolescents who play sports with repeated bending backwards (extension) movements (e.g. gymnastics, football, wrestling). It often goes undetected but may be detected if symptoms develop in adulthood. This type of spondylolisthesis is more common in males.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis occurs from progressive age-related changes that cause a change in stability creating the positional change of one vertebra over another. It is a slowly occurring process and often the spine adapts as a result. This occurs more in adults, especially women and those who are obese.

Traumatic spondylolisthesis occurs following a fracture in the facet joint structure of the vertebra and is caused by an accident/trauma.

Pathological spondylolisthesis occurs if the bone is affected by bone or connective tissue disorders, infection or tumour.

Symptoms

- Intermittent persistent low back pain

- May lead to radiculopathy or claudication (pain, weakness and/or numbness/tingling down the leg/s)

- Worse with activity

- Backward (extension) movement

- Tender to touch locally at the specific level on the spine

- Better with rest

- Muscle spasms – mostly in back and hamstrings (muscle in the back of the thighs)

- Pain and fatigue with walking and standing

- May have difficulty walking

- Loss of bowel or bladder control (rarely)

Diagnosis

- Your history, pain behavior and physical testing will be assessed.

- X-Rays may be performed in a variety of positions to assess for spondylolisthesis if the grade and stability need to be determined to direct further care.

- An MRI will be required rarely, usually only if you have associated leg pain or other symptoms, or if soube surgery is necessary.

Treatment

Most patients with symptomatic spondylolysis and low-grade (mild-moderate) spondylolisthesis improve with conservative treatments and can gradually return to sports and other activities.

Conservative treatment

Relative rest and avoiding sports that exert excessive stress on the spine;

- Light exercise (e.g. walking)

- NSAIDS (Advil/Ibuprofen)

- Heat

- Bracing may be required

- Physiotherapy

- Progressive exercises focusing on forward bending (flexion) exercises and core strengthening which have been shown to get the best results.

- General fitness activity such as walking, cycling, swimming, aqua-fit to gradually include more sport specific training (if necessary) as you heal.

- You will likely be told to avoid back-bending (extension) activities for a period of time.

You can try the following basic exercises for this condition. If they aggravate your symptoms, please discontinue and seek advice from a health professional.

Surgical treatment

Spine surgery is only considered for patients with unstable spondylolisthesis with back pain that has not improved or leg dominant pain due to pinched nerves, and if symptoms are not improving despite a period of good quality conservative treatment. The goal of the spine surgery is to take pressure off the nerves and stabilise the spine.

Usually the surgical procedure is to do a

spinal fusion procedure. A small bone graft is taken from your own body or donor, or a synthetic substance is used, to promote bone growth between the affected segments of the spine and fuse the vertebrae together. The surgeon will need to use special hardware such as screws, rods or cages to support the spine as the fusion heals, which will remain in place permanently. Depending on whether one level or more of the spine is fused will determine the required length of stay and recovery will normally take at least 6-8 weeks.

A fracture (a break in the bone) may occur in the spine because of trauma, but most frequently occurs because of osteoporosis.

A traumatic spinal fracture can be a serious injury accompanied by other injuries that require emergency treatment. There is a possibility that the spinal cord can be injured resulting in permanent damage, although this is rare.

Osteoporosis is a slowly progressing condition associated with aging, where the bones weaken due to a loss of minerals in the bone. Spinal fractures caused by osteoporosis tend to be compression fractures, where the bone becomes squashed and loses height as a response to the pressure. This tends to be less serious than traumatic fractures, and heal without any serious consequences. However, it can happen very suddenly as a result of a fall, moving to standing from sitting, bending or reaching forward, from a sneeze or a cough for example. Sometimes people are not aware of theses fractures as they do not always create pain.

The most often affected area is the junction between the mid and low back (thoracic and lumbar). There may be a loss of height or a Dowager’s hump may develop (a severely rounded upper back).

Women are affected by osteoporotic fractures 6 times more than men. Some post-menopausal women have rapid loss of bone after menopause which causes osteoporosis. Age-related bone loss is also a cause of osteoporosis and affects patients >70 years of age.

Diagnosis

Your symptom nature, history and physical exam, and possibly an X-Ray of your spine, are required to confirm a fracture. Sometimes a bone scan, CT scan and/or MRI are also performed to help establish the cause of the fracture.

Those at risk of osteoporosis can benefit from screening. This involves a bone mineral density scan which highlights areas of weakened bone so that it can be treated. Normally this involves dietary supplement of vitamin D, calcium etc.

Causes

- Menopause

- Low body weight or recent significant weight loss

- Hyperthyroidism

- Age (more common over 65 years)

- Long term use of corticosteroids (due to certain diseases like rheumatoid arthritis)

- Genetics

- Smoking

- Heavy alcohol consumption

- Inadequate nutrition

- Lack of weight-bearing exercise

Symptoms

- Acute onset of local back pain (can be dull or sharp) felt where the fracture is located

- Pain may radiate to the stomach or along the ribs

- Worse with movement and changing position

- Better with rest or lying down

- Pain at night – difficulty sleeping

- Intolerance to standing still or walking slowly - needing to walk fast or use walking aids

Conservative treatment

Most people who have a compression fracture will get better within 3 months with conservative management:

- Activity modification

- Pain relief medication (Tylenol/Acetaminophen)

- Bracing may be occasionally used

- Avoidance of heavy lifting

- Use of walking aid (walking poles, walker with integrated seat)

- Review with your doctor to lessen the risk of future fractures: e.g. dietary supplements, hormone replacement therapy, medications to treat osteoporosis (Fosamax, Didrocal, Actonel)

During recovery it is important to understand that hurt does not equal harm and that while the fracture is painful, it is important to move and that this is not causing long term harm.

A physiotherapist or other therapeutic professional can help guide you through a rehab program if you feel you need advice and guidance.

You can try the following basic exercises for this condition. If they aggravate your symptoms, please discontinue and seek advice from a health professional.

Prone Lie on Pillows

Knee to Chest

Supine Twist Beginner

Clams

Surgical treatment

Spine surgery is only required if a fracture is not stable and causes severe unrelenting pain that is not improving. This is rare. Vertebroplasty, or Kyphoplasty, are minimally invasive treatments for patients with severe pain despite trial of conservative measures. These techniques involve a method to help stabilize the fracture by the injection of “bone cement” into the vertebral body guided by X-Ray.

Scoliosis

Scoliosis is a deformity that develops in the structure of the spine that causes it to adopt an abnormal curve and/or a rotation in alignment. Usually this is a sideways curve but it can be in any direction. This creates muscle imbalance, and uneven stress and strain on the spine structures, which can cause “mechanical back pain”. If the scoliosis is severe it can cause back pain, difficulty breathing, heart problems and nerve/spinal cord compression, although the latter are very rare. It is also possible to have scoliosis without pain.

Scoliosis is measured by X-Ray, calculated in degrees and compared to “normal”. Studies show that an adults with a curve <30° is considered moderate, and tends to remain the same over time, while those with a curve >50° are more likely to progress.

Causes

There are different types of scoliosis

- Idiopathic scoliosis (“idiopathic” means there is no known cause). This type of scoliosis with no known cause accounts for 80% of scoliosis cases. It develops over time, often appearing during an adolescent growth spurt and it tends to run in families (in 30% of cases).

- Congenital scoliosis is the type of scoliosis you are born with. It begins as the spine forms before birth.

- Neuromuscular scoliosis is caused by any medical condition that affects the nerves and muscles around your spine (e.g. muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury) to cause scoliosis.

- Degenerative scoliosis - As we age, it is also possible that scoliosis will develop as a result of normal age-related degeneration of the spinal structures (bones and discs).

Diagnosis

Your symptom nature, history and physical exam, with possibly an X-Ray of your spine may be required to confirm a scoliosis.

Symptoms

Symptoms are variable, dependent on the size and location of the scoliosis.

- Minimal or no pain at all

- Back pain

- Uneven posture

- Difference in shoulder height

- Difference in hip height

- Asymmetrical chest

- Increased muscle on one side of the spine (visible when bent forward)

- Poor tolerance to certain postures or activities – muscle fatigue

- Leg pain and or numbness as well as intermittent claudication

Conservative treatment

In most cases symptoms are usually mild and shown to be well controlled with conservative treatment.

- Regular low impact cardiovascular exercise e.g. biking, swimming

- NSAIDs (Advil/Ibuprofen) and/ or pain relief medication (Tylenol/Acetaminophen)

- Bracing – a specially designed back brace to try to limit scoliosis progression may be prescribed to adolescents as their spine grows

- Physiotherapy or other active rehabilitation

- Education on self-management

- Exercise prescription: stretching, strengthening, general fitness activities and deep breathing. This will ensure your spine remains flexible, strong and decrease fatigue.

- Massage therapy for soft tissue release

- Observation – your doctor will monitor the progression of your scoliosis over time

You can try the following basic exercises for this condition. If they aggravate your symptoms, please discontinue and seek advice from a health professional.

Bridge

Clams

Prayer Stretch

Modified Side Plank

Surgical treatment

Spine surgery is considered only if there is postural imbalance as a result of the scoliosis or if there is associated radiating pain to the legs (e.g. intermittent claudication). The goal is to restore sagittal balance e.g. alignment of head over pelvis, which can help to relieve back pain, improve the radiating leg symptoms and claudication as well as correct the deformity. The goal is not necessarily to “straighten” the spine.

Surgical options are based on the cause of the symptoms and the size and direction of the scoliosis. The surgical procedure is usually a combination of a decompression (making space for the nerves by removing the smallest amount of bone and tissue in the problem area) and fusion. Fusion may use a bone graft (a small amount of bone that can be taken from your own body or a donor), and/ or a synthetic substance which are used to promote bone growth to bridge and fuse the affected vertebrae together after they are realigned. The surgeon will also need to use special hardware such as screws, rods or cages to support the spine as the fusion heals which will stay in place permanently preventing movement at the fused segments of the spine.

Spine surgery can be complex if the scoliosis is large, and recovery will take many months, with some long-term restrictions to the way you will be able to move and function.